PyPet Battle

Contents

PyPet Battle#

The game you’re going to make takes our old PyPets and has them battle until one of them wins.

Table of Contents

Part 1. Create a New Script#

First, we’re going to create a new script based off of the template we worked on in the Dragon Realm lesson.

Part 1.1: Download the Template#

In the Console

We’ll use a program called curl which is used to communicate with web

servers.

curl -O https://raw.githubusercontent.com/alissa-huskey/python-class/master/pythonclass/template.py

Part 1.2: Add the Script#

Now we’ll use the cp command to copy the script.

In the Console

cp template.py battle.py

Then follow the instructions in Repl.it Tips to edit your

.replit file to point to your new script.

Part 1.3: Basic script setup#

Now let’s change the script docstring at the beginning of the file to a description of the game. Copy these rules rules from here:

4"""

5PyPet Battle Game:

6

7[ ] Two fighters are randomly chosen from a list of PETS, each starting with a

8 health of 100

9[ ] Print out details about the chosen fighters

10[ ] Each fighter takes a turn attacking the other until one fighter wins.

11 - Each attack will have a description and do randomly selected amount of

12 damage between 10-30

13 - Each attack will print out the description of the attack, the damage it

14 did, and the health of each fighter at the end of the turn

15 - Whoever reaches 0 first loses and the other player wins.

16[ ] At the end of the game, announce the winner

17"""

18

Change the docstring for the main() function:

54def main():

55 """PyPet Battle Game"""

And let’s change the print statement in the main() function to

something more fitting for this game like maybe:

54def main():

55 """PyPet Battle Game"""

56 print("Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

Now run your script and let’s see it go!

Part 2. Make a function outline#

We’re going to approach this a little differently–we’re going to take a guess at what we think the game will look like and write minimal functions for those parts. We’re going to do a version of “write a function and call it”, except for now the functions will be placeholders where we will put future code.

If we look at the game description in the script docstring, we get a pretty good idea of how the script might look.

Part 2.1: Choose the fighters#

[ ] Two fighters are randomly chosen from a list of PETS, each starting with a

health of 100

We need a function that will choose two items from the PETS list and return

them.

44def lotto():

45 """Return two randomly chosen PETs"""

In main() add a line to call the new lotto() function, then assign the

results to a variable named fighters.

66def main():

67 """PyPet Battle Game"""

68 print("Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

69

70 fighters = lotto()

Let’s get rid of the rest of the comments under the # Functions comment line,

then add a new comment heading under it: top-level game functions.

39# ## Functions ###############################################################

40#

41# ### top-level game functions ###

42#

43

Then add the lotto() function. For now, it will only have the docstring, and

return an empty list ([]).

44def lotto():

45 """Return two randomly chosen PETs"""

46 return []

Part 2.2: Introduce the fighters#

Next we’ll need a function to introduce the fighters.

[ ] Print out details about the chosen fighters

Under the end of the lotto() function add an intro() function, which will

take one argument fighters. This function won’t return anything so it one

will just contain the docstring for now.

49def intro(fighters):

50 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

In main() add a line to call the new intro() function with the argument

fighters.

66def main():

67 """PyPet Battle Game"""

68 print("Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

69

70 fighters = lotto()

71 intro(fighters)

Part 2.3: The fight#

Now the fighters fight!

[ ] Each fighter takes a turn attacking the other until one fighter wins.

Add a fight() function that that takes the list of fighters as an argument.

We know it will return a dictionary from the PET list, so as a placeholder

return an empty dictionary ({}).

53def fight(fighters):

54 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

55 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

56 return {}

Let’s add it to the main() function add a line to call our new fight()

function and assign the results to a variable named winner.

66def main():

67 """PyPet Battle Game"""

68 print("Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

69

70 fighters = lotto()

71 intro(fighters)

72 winner = fight(fighters)

Part 2.4: Winner, winner#

Now we wrap up the game by announcing the winner.

[ ] At the end of the game, announce the winner

Add an endgame() function that will take the winner as an argument. We know

it will return a dictionary from the PET list, so as a placeholder return an

empty dictionary ({}).

59def endgame(winner):

60 """Takes a PET (winner) and announce that they won the fight"""

In main() add a line to call the new endgame() function with the argument

winner.

66def main():

67 """PyPet Battle Game"""

68 print("Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

69

70 fighters = lotto()

71 intro(fighters)

72 winner = fight(fighters)

73 endgame(winner)

By now you should have a pretty good idea of how the script will end up working and what each part will do.

Even though you won’t expect to see any changes in output go ahead and run your script anyway to make sure there are no errors.

Part 3. pets module#

One of the handy things about code is that it is reusable. So we’re going to make a pets module that we could reuse in future projects.

Part 3.1: Create a pets.py file#

Make a new file named pets.py. Add a docstring then copy the following PICS

dictionary into it.

1"""Pets Data"""

2

3# a hash of pet pics

4# species: pic

5PICS = {

6 'dragon': "/|\\{O_O}/|\\",

7 'cat': "=^..^=",

8 'fish': "<`)))><",

9 'owl': "{O,o}",

10 'snake': "_/\\__/\\_/--{ :>~",

11 'bat': "/|\\^..^/|\\",

12 'monkey': "@('_')@",

13 'pig': "^(*(oo)*)^",

14 'mouse': "<:3 )~~~",

15 'bird': ",(u°)>",

16 'cthulhu': "^(;,;)^",

17 'fox': "-^^,--,~",

18}

19

Part 3.2: Add your pets list#

A. Review#

By now you know how to add simple strings or integers to lists:

14CAVES = ["right", "left"]

In the pypet project, you also learned how to add dictionary items to a list using variables.

12cat = {

13 "name": "Fluffy",

14 "hungry": True,

15 "weight": 9.5,

16 "age": 5,

17 "pic": "(=^o.o^=)_",

18}

19

20mouse = {

21 "name": "Mouse",

22 "age": 6,

23 "weight": 1.5,

24 "hungry": False,

25 "pic": "<:3 )~~~~",

26}

27

28pets = [cat, mouse]

In the next section we’ll learn how to make a nested list of literal dictionaries.

B. Nested lists#

We could add our list of pets the same way we did in the pypet game.

1FLUFO = {"name": "Flufo"}

2SCALEY = {"name": "Scaley"}

3

4PETS = [FLUFO, SCALEY]

You can also embed dictionaries in a list without using variables by putting the dictionary where you would have put the variable otherwise.

1PETS = [{"name": "Flufo"}, {"name": "Scaley"}]

When you’re dealing with a nested list or dictionary it’s a good idea to split up the list items so that each dictionary item is on a line of its own. This makes it a lot easier to read.

1PETS = [

2 {"name": "Flufo"},

3 {"name": "Scaley"}

4]

In all three of the above examples the PETS list is exactly the same.

You can access an element of a nested list the way you normally would with the

syntax variable[index].

5pet = PETS[3]

6print(pet['name'], "says hello!")

You can access also access nested dictionary values from a list by adding the

[] reference straight to the end of the previous [] with the syntax

variable[index][key].

5print(PETS[3]['name'], "says hello!")

C. In pets.py#

Use what you just learned to add pet dictionaries to a list named PETS in

pets.py. Each dictionary should have the keys name and species.

20PETS = [

21 {'name': "Flufosourus", 'species': "cat"},

22 {'name': "Scaley", 'species': "fish"},

23 {'name': "Count Chocula", 'species': "bat"},

24 {'name': "Curious George", 'species': "monkey"},

25]

Part 3.3: Import your module#

In order to use PICS and PETS in your battle game you’ll need to import

them.

A. Partial imports#

By now you know how to import a whole module at once using the import

statement. And you know that to access the things in that module you use the

syntax module.object.

1import random

2

3number = random.randint(0, 100)

You can also import objects one at a time from a module with the syntax:

from <module> import <object>

This allows you to only import part of a module, and also imports it into the global namespace. That means that when we refer to the imported functions (or in this case, variables) we don’t need to use the module name.

1from random import randint

2

3number = randint(0, 100)

B. At the top of battle.py#

Now import PICS and PETS in the # Imports section at the top of

battle.py:

29# ### Imports ################################################################

30

31from pets import PICS, PETS

Part 4. Fill in the lotto() function#

Now let’s start making the our functions actually do things, starting with the

lotto() function.

Part 4.1: Import the random module#

We’ll need the random module in the lotto() function.

At the end of our Imports section add a line to import it.

29# ### Imports ################################################################

30

31from pets import PICS, PETS

32import random

Part 4.2: Write the lotto() function#

Then we’ll fill in the lotto() function.

First we’ll use a new function random.shuffle to randomly reorder the contents

of the PETS list. Then we’ll return a new list that contains the first two

elements of PETS.

The new lotto() function should look like this.

42def lotto():

43 """Return two randomly chosen PETs"""

44 # randomly reorder the PETS list

45 random.shuffle(PETS)

46

47 # return the first two items in the PETS list

48 return [PETS[0], PETS[1]]

Run your script to make sure it works.

Part 5. Fill in the intro() function#

Here’s a preview of what our new intro() function will look like when we’re

done.

intro()

58def intro(fighters):

59 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

60

61 print("\n Tonight...\n")

62 time.sleep(DELAY)

63

64 # announce the fighters

65 header = f"*** {fighters[0]['name']} -vs- {fighters[1]['name']} ***"

66 print(header.center(WIDTH, " "), "\n\n")

67

68 # pause for input

69 input("ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!")

70 print("." * WIDTH, "\n")

Part 5.1: Import time#

We’ll use the time module to add some suspense to our announcement. At the

end of the # Imports section add:

29# ### Imports ################################################################

30

31from pets import PICS, PETS

32import random

33import time

Part 5.2: Add DELAY and WIDTH#

Then we’ll need DELAY and WIDTH global variables. Add these to the end of

the # Global Variables section.

35# ## Global Variables ########################################################

36

37# the number of seconds to pause for dramatic effect

38DELAY = 1

39

40# the max width of the screen

41WIDTH = 55

Part 5.3: Print “Tonight…” then sleep#

The first part of the intro() function prints out the word “Tonight…” then

calls the time.sleep() function.

Add this to the end of the intro() function.

def intro(fighters):

"""Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

print("\n Tonight...\n")

time.sleep(DELAY)

Part 5.4: Announce the fighters using f-strings#

A. f-strings#

We’ve learned how to concatenate strings using the + operator.

greeting = "Good " + time_of_day + " to you."

Now we are going to learn about string interpolation which means to embed code in a string. In Python, this is done with a special syntax called f-strings.

The string starts with the letter f immediately before the string. A single

quote or double quote as usual starts and ends the string. And here’s the fancy

part: any code you want to embed (usually a variable name) is put inside of

curly braces.

The same string from above could be written as:

1greeting = f"Good {time_of_day} to you."

B. In intro()#

Let’s use this new syntax to make a variable called header that will contain

the names of the fighters.

At the end of the intro() add the following

58def intro(fighters):

59 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

60

61 print("\n Tonight...\n")

62 time.sleep(DELAY)

63

64 # announce the fighters

65 header = f"*** {fighters[0]['name']} -vs- {fighters[1]['name']} ***"

There’s a lot going on in that f-string, so let’s go through it in detail.

f"starts the f-string***is a literal string{starts the codefighters[0]gets the first element of the fighters list['name']gets thenamevalue from that pet’s dictionary-vs -is a literal string{starts the codefighters[1]gets the second element of the fighters list['name']gets thenamevalue from that pet’s dictionary***is a literal string"ends the f-string

So of our fighters list contained:

fighters = [

{ 'name': "Curious George" },

{ 'name': "Ol' Yeller" },

]

Then the value of the header variable would be:

*** Ol' Yeller -vs- Curious George ***

Part 5.5: Print the announcement using str.center()#

Python has a handy function on str objects for centering text. It takes a

width argument, for the total length of the resulting string. We’ll use the

WIDTH variable defined earlier.

Finally, we’ll add two newlines (\n) to the end of the print statement.

At the end of the intro() function add the following:

58def intro(fighters):

59 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

60

61 print("\n Tonight...\n")

62 time.sleep(DELAY)

63

64 # announce the fighters

65 header = f"*** {fighters[0]['name']} -vs- {fighters[1]['name']} ***"

66 print(header.center(WIDTH, " "), "\n\n")

Part 5.6: Pause for input#

Let’s give the player a chance to do something before the game continues. We won’t actually do anything with the player feedback in this game. We just want to give the player something to do.

We’ll call the input() function with a prompt.

At the end of the intro() function add:

58def intro(fighters):

59 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

60

61 print("\n Tonight...\n")

62 time.sleep(DELAY)

63

64 # announce the fighters

65 header = f"*** {fighters[0]['name']} -vs- {fighters[1]['name']} ***"

66 print(header.center(WIDTH, " "), "\n\n")

67

68 # pause for input

69 input("ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!")

Part 5.7: Draw a line#

Python has a neat way to repeat a string, with the * operator. We’ll use this

handy trick to easily draw a line of a particular size. In this case, we’ll

make the line out of dots (.) just to mix it up. Then we’ll add an extra

newline (\n) at the end of the print statement.

At the end of the intro() function under line 64 add:

58def intro(fighters):

59 """Takes a list of two PETs (fighters) and prints their details"""

60

61 print("\n Tonight...\n")

62 time.sleep(DELAY)

63

64 # announce the fighters

65 header = f"*** {fighters[0]['name']} -vs- {fighters[1]['name']} ***"

66 print(header.center(WIDTH, " "), "\n\n")

67

68 # pause for input

69 input("ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!")

70 print("." * WIDTH, "\n")

Run your script and see what you’ve got!

Part 6. Outline the fight() function#

The fight() function has a lot to do, so we’ll start by writing a bit of an

outline for it.

Here’s a preview of what those functions will look like when we’re done.

fight()

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

82

83 # check for a loser (placeholder)

84 winner = random.choice(fighters)

85

86 # print a line at the end of every round

87 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

88

89 #

90 # ### end of fighting rounds

91

92 # return the winner

93 return winner

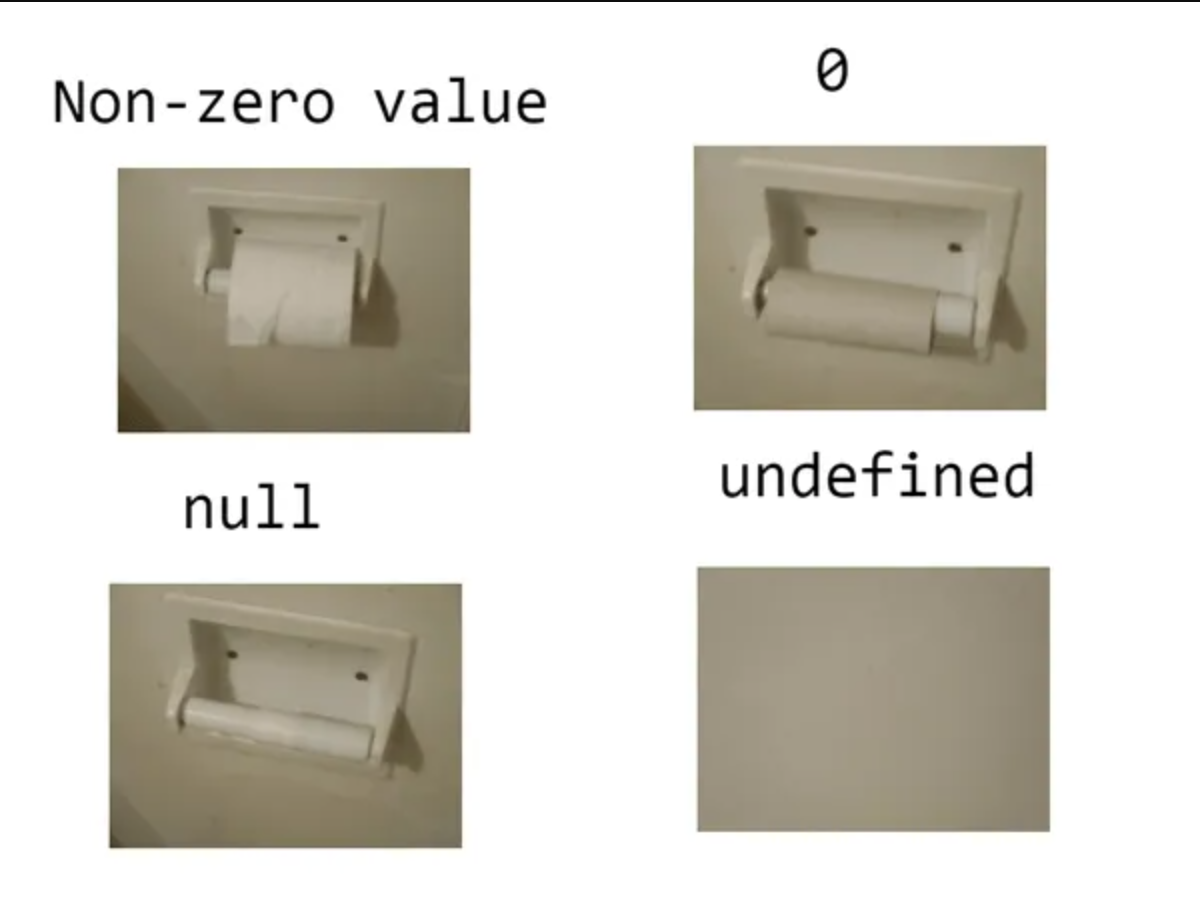

Part 6.1: The None type#

A. Null values#

Python has a special type called None, which is what is known in programming

as a null value.

Sometimes we need to know the difference between a value set to nothing, and when it is set to zero or an empty string.

Imagine we had a program that would print out how many apples the user had. If the program didn’t know how many apples, it would ask them.

We would need to be able to tell if the user had told us that they had zero

apples, or if the user hadn’t yet told us how many they have. That’s where

None comes in.

Here is a handy picture to help clarify.

B. In fight()#

Start your fight() function by setting the variable winner to None.

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

Part 6.2: Keep going until there’s a winner#

We’re going to write a while loop to keep fighting until there’s a winner.

We’ll use the None type to tell that there is still no winner.

A. while loops#

A while loop is a conditional statement. That means that, like an

if statement it uses a condition to decide what to do with the

block of code that belongs to it.

But where an if statement will only execute its code block if the condition

is met, a while loop will keep repeating its code block for as long as the

condition is met.

1i = random.randint(0, 100)

2

3if i < 50:

4 print(f"You have: {i}")

1i = 0

2

3while i < 50:

4 i = i + 1

5 print(f"You have: {i}")

In this if statement i would be printed once, and only if it happened to be less

than 50.

In this while loop i would be printed over and over again until it reaches

50.

B. In fight()#

We’re going to use a while loop to keep going for as long as the value of winner is None.

Add to your fight() function:

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

Part 6.3: Add a placeholder winner#

Just so we can test our script without looping forever, we’ll put a placeholder

in the loop that randomly selects a winner from our list of fighters. (This

means that the loop will only run once for now.)

We’ll use the random.choice() function, which randomly selects an element

from a list.

In fight()#

Add to your fight() function inside the while loop:

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

82

83 # check for a loser (placeholder)

84 winner = random.choice(fighters)

Part 6.4: Print a round-end line#

So we can see that when a round happens, we’ll add a line at the end of every loop.

In fight()#

Add to your fight() function inside the while loop:

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

82

83 # check for a loser (placeholder)

84 winner = random.choice(fighters)

85

86 # print a line at the end of every round

87 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

Part 6.5: return the winner#

A. In fight(), around the while loop#

Add comments at the beginning and end of the while loop so we can tell where the code is that executes each round.

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

82

83 # check for a loser (placeholder)

84 winner = random.choice(fighters)

85

86 # print a line at the end of every round

87 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

88

89 #

90 # ### end of fighting rounds

B. In fight(), after the while loop#

Now change the last line of your function to return winner instead of an

empty dictionary.

73def fight(fighters):

74 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

75 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

76

77 winner = None

78

79 # ### rounds of the fight

80 #

81 while winner is None:

82

83 # check for a loser (placeholder)

84 winner = random.choice(fighters)

85

86 # print a line at the end of every round

87 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

88

89 #

90 # ### end of fighting rounds

91

92 # return the winner

93 return winner

Notice that the return statement is outside of the while loop. That is because we want to make sure that all the rounds are finished before exiting the function.

Part 7. Print the fighter health#

In this section we will print out the fighters health for each round. Here’s what the game output will look like when we’re done:

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Count Chocula -vs- Curious George ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Count Chocula /|\^..^/|\ 100 of 100

Curious George @('_')@ 100 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

We’ll make changes to the fight() and main() functions and add show() and

setup() functions.

Here’s a preview of what those functions will look like when we’re done.

code

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 winner = None

98

99 # ### rounds of the fight

100 #

101 while winner is None:

102

103 # check for a loser (placeholder)

104 winner = random.choice(fighters)

105

106 # print updated fighter health

107 print()

108 for combatant in fighters:

109 show(combatant)

110

111 # print a line at the end of every round

112 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

113

114 #

115 # ### end of fighting rounds

116

117 # return the winner

118 return winner

128def main():

129 """PyPet Battle Game"""

130 print("\nWelcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

131

132 fighters = lotto()

133 setup(fighters)

134

135 intro(fighters)

136 winner = fight(fighters)

137 endgame(winner)

51def setup(pets):

52 """Takes a list of pets and sets initial attributes"""

53 for pet in pets:

54 pet['health'] = MAX_HEALTH

55 pet['pic'] = PICS[pet['species']]

58def show(pet):

59 """Takes a pet and prints health and details about them"""

60 name_display = f"{pet['name']} {pet['pic']}"

61 health_display = f"{pet['health']} of {MAX_HEALTH}"

62 rcol_width = WIDTH - len(name_display) - 1

63 print(name_display, health_display.rjust(rcol_width))

Part 7.1: Print each fighter’s info#

Let’s make a function that will eventually print out the health for a pet and

call it show().

Part 7.1: Add show()#

A. Add # pet functions header#

At the top of the Functions section let’s add a new comment section for

# pet functions.

45# ## Functions ###############################################################

46

47# ### pet functions ###

48#

49

50

B. Add show()#

Under your new header add a show() function that takes one argument pet.

58def show(pet):

59 """Takes a pet and prints health and details about them"""

Part 7.2: Print info each round#

You already know that what goes on inside the while loop in fight()

represents what happens each round of a fight.

We’ll want to print out the health for each fighter, and have it happen at the end of every round.

To do this we’ll use a for loop and in it we’ll call the show() function.

In fight(), inside the while loop#

In the fight() function, inside the for loop and just above where you print a

line:

Call the

print()function with no arguments to print a blank lineWrite a for loop that iterates over the

fightersand uses the variablecombatantInside the for loop, call the

show()function with the argumentcombatant

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 winner = None

98

99 # ### rounds of the fight

100 #

101 while winner is None:

102

103 # check for a loser (placeholder)

104 winner = random.choice(fighters)

105

106 # print updated fighter health

107 print()

108 for combatant in fighters:

109 show(combatant)

110

111 # print a line at the end of every round

112 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

113

114 #

115 # ### end of fighting rounds

116

117 # return the winner

118 return winner

Part 7.3: MAX_HEALTH#

Add a MAX_HEALTH variable at the end of the Global Variables section add to

keep track of the maximum health.

35# ## Global Variables ########################################################

36

37# the number of seconds to pause for dramatic effect

38DELAY = 1

39

40# the max width of the screen

41WIDTH = 56

42

43MAX_HEALTH = 100

Part 7.4: Setup setup()#

To print the fighter info, we’ll need pets health and pic. To do this we’ll add

a new function called setup() then call it from main().

A. Add setup()#

Under the # pet functions header add a setup() function.

51def setup(pets):

52 """Takes a list of pets and sets initial attributes"""

B. In main()#

Now we’ll call it from inside main() and pass it the argument fighters.

This should go just after the line where fighters is assigned.

128def main():

129 """PyPet Battle Game"""

130 print("\nWelcome to the THUNDERDOME!")

131

132 fighters = lotto()

133 setup(fighters)

134

135 intro(fighters)

136 winner = fight(fighters)

137 endgame(winner)

Part 7.5: Initialize fighter info#

In the setup() function, use a for loop to assign the 'health' and 'pic'

keys in each dictionary in the fighters list.

A. Set pet health#

For each pet, we’ll set the health to MAX_HEALTH.

Use a for loop to iterate over

petswith the variablepetAssign

pet['health']toMAX_HEALTH

51def setup(pets):

52 """Takes a list of pets and sets initial attributes"""

53 for pet in pets:

54 pet['health'] = MAX_HEALTH

B. Getting the pic#

We’ll need to get the picture for each pet. In order to do that we’ll use the

pet['species'] as the key to the PICS dictionary.

One way to do that is to assign the value of pet['species'] to a variable

species which we can then use as the key to PICS.

1species = pet['species']

2print(PICS[species])

You can avoid setting a temporary variable by putting pet['species'] where

you would have put the variable.

1print(PICS[pet['species']])

These both have the same effect, so it’s up to you which you prefer.

C. In setup(), inside the for loop#

Use the syntax that you just learned to get the pet pic from the PICS

dictionary using the pet['species'] key. Assign it to pet['pic'].

51def setup(pets):

52 """Takes a list of pets and sets initial attributes"""

53 for pet in pets:

54 pet['health'] = MAX_HEALTH

55 pet['pic'] = PICS[pet['species']]

Part 7.6: Fill in the show() function#

Now that each pet in the fighters list has all of the information we need

we can fill in the show() function to actually print the name, pic and

health.

In show()#

Assign a

name_displayvariable to the stringname picAssign a

health_displayvariable to"x of y"health, wherexthepet["health"]andyisMAX_HEALTHPrint both variables

58def show(pet):

59 """Takes a pet and prints health and details about them"""

60 name_display = f"{pet['name']} {pet['pic']}"

61 health_display = f"{pet['health']} of {MAX_HEALTH}"

62 print(name_display, health_display)

When you run your program your output should look something like this:

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Curious George -vs- Count Chocula ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Curious George @('_')@ 100 of 100

Count Chocula /|\^..^/|\ 100 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

Part 7.7: Make columns with str.rjust()#

Now let’s get a little fancy let’s and right-align the health display.

A. Right aligning#

To right align text we can use the built in .rjust() method on str objects.

It works just like like str.center() and takes a width variable.

Here’s an example that prints a list of numbers and uses .rjust() to right

align them to a width of 30.

B. In show()#

But wait, in this case we want to print part of the line left aligned, and part of it right aligned. How do we manage that?

To accomplish this, we’ll need to figure out how long the left-aligned part of

the string is and use that to adjust the width passed to .rjust().

Subtract the length of

name_displayfromWIDTHSubtract

1more to account for the space thatprint()addsAssign the result to a variable

rcol_widthInside of

print()call the.rjust()method onhealth_displaywith the argumentrcol_width

58def show(pet):

59 """Takes a pet and prints health and details about them"""

60 name_display = f"{pet['name']} {pet['pic']}"

61 health_display = f"{pet['health']} of {MAX_HEALTH}"

62 rcol_width = WIDTH - len(name_display) - 1

63 print(name_display, health_display.rjust(rcol_width))

Now when you run your script it should look something like this:

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Flufosourus -vs- Curious George ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Flufosourus =^..^= 100 of 100

Curious George @('_')@ 100 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

Part 8. Choose who attacks#

Continuing with the fight() function, we need switch back and forth between

the two fighters for who attacks each round.

Here’s a preview of the updated fight() function:

fight()

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 # winning fighter

98 winner = None

99

100 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

101 current = 0

102

103 # ### rounds of the fight

104 #

105 while winner is None:

106 # pick whose turn it is

107 attacker = fighters[current]

108 rival = fighters[not current] # noqa

109

110 # pause for input

111 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

112

113 # check for a loser (placeholder)

114 winner = random.choice(fighters)

115

116 # print updated fighter health

117 print()

118 for combatant in fighters:

119 show(combatant)

120

121 # print a line at the end of every round

122 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

123

124 # flip current to the other fighter for the next round

125 current = not current

126

127 #

128 # ### end of fighting rounds

129

130 # return the winner

131 return winner

Part 8.1: Set a current variable#

We’re going to use a variable current to keep track whose turn it is

according to their index number the fighters list.

Remember, lists have index numbers that start at 0 and can be accessed like

this: mylist[0].

In fight(), before the while loop#

Add the current variable to the top of the fight() function, before the

while loop and set it to 0.

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 # winning fighter

98 winner = None

99

100 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

101 current = 0

Part 8.2: Pick the attacker#

A. Toggling with not#

We’ve used the not operator in if statements before. For example:

if not False:

print("double negatives ftw!")

double negatives ftw!

not is really shorthand for False ==.

That means another way to write the above is:

if False == False:

print("double negatives ftw!")

double negatives ftw!

When we use a comparison operator like not or == it is part of an

expression that evaluates to a bool value.

That means we can use a standalone condition to get either True or False.

True == True

True

False == True

False

That means that if you want to get the opposite of a bool value, just put

not in front of it.

not True

False

not False

True

We can use this trick to alternate back and forth between True and False in

a loop.

alternating = True

for i in range(0, 5):

print(alternating)

alternating = not alternating

True

False

True

False

True

We’ll use this trick to alternate whose turn it is in the fight() function.

B. bool and int#

Under the hood a bool is just a special kind of int that has a name in

Python.

Specifically, False is 0 and True is 1.

False == 0

True

True == 1

True

You use True and False as an int in ways that might surprise you.

True + True + True

3

One example is that you can use True and False as index numbers in a list.

options = ["No", "Yes"]

print(options[True])

Yes

That means that we can use the bool result of not current to pick a pet

from the fighters list.

C. In fight(), at the beginning of the while loop#

We’ll need to pick whose turn it is at the beginning of each round. That means this code needs to be the first lines inside the while loop.

Assign the

fighters[current]to the variableattackerAssign the

fighters[not current]to the variablerival

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 # winning fighter

98 winner = None

99

100 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

101 current = 0

102

103 # ### rounds of the fight

104 #

105 while winner is None:

106 # pick whose turn it is

107 attacker = fighters[current]

108 rival = fighters[not current] # noqa

Part 8.3: Switch fighter’s turn#

We’ll use the not trick again at the end of the while loop to switch back

and forth between the two fighters.

In fight(), at the end of the while loop#

In the fight() function at the end of the while loop, set current to be

the opposite of itself.

113 # check for a loser (placeholder)

114 winner = random.choice(fighters)

115

116 # print updated fighter health

117 print()

118 for combatant in fighters:

119 show(combatant)

120

121 # print a line at the end of every round

122 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

123

124 # flip current to the other fighter for the next round

125 current = not current

126

127 #

128 # ### end of fighting rounds

129

130 # return the winner

131 return winner

Part 8.4: Print the attacker#

Finally we want to print out the attacker for each round. We prompt for input again, but once again this is just to give the player a chance to do something–we don’t do anything with the input.

In fight(), inside the while loop#

In the fight() function just after the line where rival is assigned add the

following.

93def fight(fighters):

94 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

95 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

96

97 # winning fighter

98 winner = None

99

100 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

101 current = 0

102

103 # ### rounds of the fight

104 #

105 while winner is None:

106 # pick whose turn it is

107 attacker = fighters[current]

108 rival = fighters[not current] # noqa

109

110 # pause for input

111 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

When you run your script your output should see a new line prompting the first pet to fight.

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Flufosourus -vs- Count Chocula ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Flufosourus FIGHT>

Flufosourus =^..^= 100 of 100

Count Chocula /|\^..^/|\ 100 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

Part 9. Attack#

In this section we’ll be adding the attack() function and making changes to the fight() function.

code

69def attack(foe):

70 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

71 damage and attack used"""

72 return 10, "smacks upside the head"

102def fight(fighters):

103 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

104 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

105

106 # winning fighter

107 winner = None

108

109 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

110 current = 0

111

112 # ### rounds of the fight

113 #

114 while winner is None:

115 # pick whose turn it is

116 attacker = fighters[current]

117 rival = fighters[not current]

118

119 # pause for input

120 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

121

122 # the attack

123 damage, act = attack(rival)

124

125 # pause for effect, then print attack details

126 time.sleep(DELAY)

127 print(f"\n {attacker['name']} {act} {rival['name']}...\n")

128

129 # pause for effect, then print damage

130 time.sleep(DELAY)

131 print(f"-{damage} {rival['name']}".center(WIDTH), "\n")

132

133 # one more pause before the round ends

134 time.sleep(DELAY)

135

136 # check for a loser (placeholder)

137 winner = random.choice(fighters)

138

139 # print updated fighter health

140 print()

141 for combatant in fighters:

142 show(combatant)

143

144 # print a line at the end of every round

145 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

146

147 # flip current to the other fighter for the next round

148 current = not current

149

150 #

151 # ### end of fighting rounds

152

153 # return the winner

154 return winner

Part 9.1: Add attack()#

We’ll need a function that picks what kind of attack to do, calculates damage

the damage and modifies the health of the rival.

We’re going to call this the attack() function, which will take one argument,

the foe.

A. Add # game event functions#

In the # Functions section after show() and setup() add a new subsection

for # game event functions.

46# ## Functions ###############################################################

47

48# ### pet functions ###

49#

50

51def setup(pets):

52 """Takes a list of pets and sets initial attributes"""

53 for pet in pets:

54 pet['health'] = MAX_HEALTH

55 pet['pic'] = PICS[pet['species']]

56

57

58def show(pet):

59 """Takes a pet and prints health and details about them"""

60 name_display = f"{pet['name']} {pet['pic']}"

61 health_display = f"{pet['health']} of {MAX_HEALTH}"

62 rcol_width = WIDTH - len(name_display) - 1

63 print(name_display, health_display.rjust(rcol_width))

64

65

66# ### game event functions ###

67#

68

B. Multiple returning and assigning#

Python functions can return nothing, a single value, or more than one values. In this case, we’re returning both the damage amount, and the attack description.

The syntax when returning multiple values is:

return <val1>, <val2>

For example

def gimme():

return (1, 2)

The syntax when assigning the results is:

<var1>, <var2> = fun()

For example:

a, b = gimme()

We’ll use this syntax in the new attack() function to return both the damage

value and a description of the attack.

C. Add attack()#

Under # game event functions add an attack() function with one argument

foe.

It should return a tuple containing two values:

an

intfor the damagea

strfor the description

For now just have it return hardcoded values.

69def attack(foe):

70 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

71 damage and attack used"""

72 return 10, "smacks upside the head"

Part 9.2: attack() in fight()#

Now in each round of the fight the rival should be attacked using the

attack() function.

In fight()#

After pausing for input call the attack() function with the argument rival.

Using multiple assignment, assign the results to damage and act.

102def fight(fighters):

103 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

104 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

105

106 # winning fighter

107 winner = None

108

109 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

110 current = 0

111

112 # ### rounds of the fight

113 #

114 while winner is None:

115 # pick whose turn it is

116 attacker = fighters[current]

117 rival = fighters[not current]

118

119 # pause for input

120 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

121

122 # the attack

123 damage, act = attack(rival)

Part 9.3: Print attack details#

Now we just need to print out all of the details of the attack. We’ll use the

time.sleep() function to add pauses between output for effect.

We’ll want to print who attacked who and how, as well as the damage that was done.

In fight()#

In the fight() function after the attack() line:

Call

time.sleep()with the argumentDELAYPrint the attackers name, the

actand the rivals name, followed by “…”Call

time.sleep()with the argumentDELAYPrint the

damageas a negative number, followed by the rivals name. Center this whole string usingWIDTHCall

time.sleep()with the argumentDELAY

114 while winner is None:

115 # pick whose turn it is

116 attacker = fighters[current]

117 rival = fighters[not current]

118

119 # pause for input

120 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

121

122 # the attack

123 damage, act = attack(rival)

124

125 # pause for effect, then print attack details

126 time.sleep(DELAY)

127 print(f"\n {attacker['name']} {act} {rival['name']}...\n")

128

129 # pause for effect, then print damage

130 time.sleep(DELAY)

131 print(f"-{damage} {rival['name']}".center(WIDTH), "\n")

132

133 # one more pause before the round ends

134 time.sleep(DELAY)

135

136 # check for a loser (placeholder)

137 winner = random.choice(fighters)

138

139 # print updated fighter health

140 print()

141 for combatant in fighters:

142 show(combatant)

143

144 # print a line at the end of every round

145 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

146

147 # flip current to the other fighter for the next round

148 current = not current

When you run your game you should see what happened in the round.

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Scaley -vs- Curious George ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Scaley FIGHT>

Scaley smacks upside the head Curious George...

-10 Curious George

Scaley <`)))>< 100 of 100

Curious George @('_')@ 100 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

Part 10. Attack, For Realsies#

In this section we’ll make the attack actually do something.

We’ll be adding global variables POWER and FIGHTIN_WORDS and filling in the

attack() function.

Here’s what the code will look like when we’re done.

code

35# ## Global Variables ########################################################

36

37# the range of damage each player can do

38#

39# this is a data type called a tuple

40# it is just like a list, except it is

41# immutable, meaning it cannot be changed

42

43POWER = (10, 30)

44

45# the number of seconds to pause for dramatic effect

46DELAY = 1

47

48# the max width of the screen

49WIDTH = 56

50

51MAX_HEALTH = 100

52

53# a list of attacks

54FIGHTIN_WORDS = (

55 "nips at",

56 "takes a swipe at",

57 "glares sternly at",

58 "ferociously smacks",

59 "savagely boofs",

60 "is awfully mean to",

61 "can't even believe",

62 "throws mad shade at",

63)

64

65

89def attack(foe):

90 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

91 damage and attack used"""

92 # choose an attack

93 act = random.choice(FIGHTIN_WORDS)

94

95 # randomly set damage

96 damage = random.randint(POWER[0], POWER[1])

97

98 # inflict damage

99 foe['health'] -= damage

100

101 # return the amount of damage attack and description

102 return damage, act

Part 10.1: The tuple type#

We’ve learned about lists and dictionaries already. These are both collections or container types. That means that they contain some number of children elements.

The tuple is another container type. It is very similar to a list, except

that it is immutable meaning that once it is defined it cannot be

changed. This is handy for global variables where only intend to read the data

in the script and never to modify it. They’re also faster and consume less

memory.

Tuples are defined using parenthesis ( ).

CAVES = ("right", "left", "middle")

Elements are accessed with index numbers (just like lists).

print(CAVES[0])

right

Tuples are immutable, so you can’t change them later.

CAVES[0] = "east"

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[16], line 1

----> 1 CAVES[0] = "east"

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

To review Python container types:

Keyword |

Creating |

Accessing |

Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

ordered, mutable |

|

|

|

ordered, immutable |

|

|

|

unordered, mutable |

|

|

|

unordered, mutable, unique |

Part 10.2: Them’s Fightin’ Words#

Let’s make a list of attacks using the tuple type we just learned about. At the end of the global variables section add the following. Feel free to change these or get creative and add your own.

53# a list of attacks

54FIGHTIN_WORDS = (

55 "nips at",

56 "takes a swipe at",

57 "glares sternly at",

58 "ferociously smacks",

59 "savagely boofs",

60 "is awfully mean to",

61 "can't even believe",

62 "throws mad shade at",

63)

64

65

Part 10.3: Pick an attack#

Now that we have some attacks to choose from, let’s edit our attack()

function to pick one.

In attack()#

Use the

random.choice()function to pick from the newFIGHTING_WORDSlist and assign it to the variableactIn the

returnstatement replace your hardcoded attack string with theactvariable

89def attack(foe):

90 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

91 damage and attack used"""

92 # choose an attack

93 act = random.choice(FIGHTIN_WORDS)

94

95 return 10, act

Part 10.4: What’s your damage#

Now we need to figure out how much damage the attack will do. First we’ll add a global variable POWER to set the possible damage range for each attack.

A. In global variables#

35# ## Global Variables ########################################################

36

37# the range of damage each player can do

38#

39# this is a data type called a tuple

40# it is just like a list, except it is

41# immutable, meaning it cannot be changed

42

43POWER = (10, 30)

B. In attack()#

Now we can use the good old randint function to randomly select a value in

that range.

Call

random.randintand pass it the two values in thePOWERtuple as arguments. Assign the result to the variabledamage

89def attack(foe):

90 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

91 damage and attack used"""

92 # choose an attack

93 act = random.choice(FIGHTIN_WORDS)

94

95 # randomly set damage

96 damage = random.randint(POWER[0], POWER[1])

C. Shortcut operators#

In this section we’ll learn about some operators to do math and assign at the same time.

In programming you often want to do some math on a value, then assign the result back to the original variable. For example:

x = 1

x = x + 1

print(x)

2

A quicker way to do this is to use the += operator.

x = 1

x += 1

print(x)

2

The same thing comes up with subtracting a value from itself.

x = 1

x = x - 1

print(x)

0

The shorthand operator for subtract and assign is -=.

x = 1

x -= 1

print(x)

0

Let’s use this operator to reduce the health of foe.

D. In attack()#

Now that we have the damage value set, we can finally inflict it upon our the

foe.

Use the

-=operator to subtractdamagefromfoe['health']In the

returnstatement replace your hardcoded damageintwith thedamagevariable

89def attack(foe):

90 """Inflict a random amount of damage is inflicted on foe, then return the

91 damage and attack used"""

92 # choose an attack

93 act = random.choice(FIGHTIN_WORDS)

94

95 # randomly set damage

96 damage = random.randint(POWER[0], POWER[1])

97

98 # inflict damage

99 foe['health'] -= damage

100

101 # return the amount of damage attack and description

102 return damage, act

Now when you run your game you should see a randomized value of damage done, and that number will actually effect one of the fighters health.

Welcome to the THUNDERDOME!

Tonight...

*** Scaley -vs- Count Chocula ***

ARE YOU READY TO RUMBLE?!

........................................................

Scaley FIGHT>

Scaley throws mad shade at Count Chocula...

-27 Count Chocula

Scaley <`)))>< 100 of 100

Count Chocula /|\^..^/|\ 73 of 100

--------------------------------------------------------

Part 11. Find The Winner#

In this section we’re going to finish the fight() function by picking the

winner.

Here’s how the function will look at the end:

fight()

132def fight(fighters):

133 """Repeat rounds of the fight until one wins then

134 Take a list of two PETs and return the winning PET"""

135

136 # winning fighter

137 winner = None

138

139 # the index in the fighters list of the attacker in each round

140 current = 0

141

142 # ### rounds of the fight

143 #

144 while winner is None:

145 # pick whose turn it is

146 attacker = fighters[current]

147 rival = fighters[not current]

148

149 # pause for input

150 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

151

152 # the attack

153 damage, act = attack(rival)

154

155 # pause for effect, then print attack details

156 time.sleep(DELAY)

157 print(f"\n {attacker['name']} {act} {rival['name']}...\n")

158

159 # pause for effect, then print damage

160 time.sleep(DELAY)

161 print(f"-{damage} {rival['name']}".center(WIDTH), "\n")

162

163 # one more pause before the round ends

164 time.sleep(DELAY)

165

166 # check for a loser

167 if rival['health'] <= 0:

168 # don't let health drop below zero

169 rival['health'] = 0

170 # set the winner, this is now the last round

171 winner = attacker

172

173 # print updated fighter health

174 print()

175 for combatant in fighters:

176 show(combatant)

177

178 # print a line at the end of every round

179 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

180

181 # flip current to the other fighter for the next round

182 current = not current

183

184 #

185 # ### end of fighting rounds

186

187 # return the winner

188 return winner

Part 11.1: Check rival health#

Instead of randomly choosing a winner, in this section we’ll pick a real one.

Fist, we want to check if the health of the rival who was just attacked has

reached zero. If it has, then we know that the winner is the other guy (the

attacker).

Also, we don’t want health be a negative number so we’ll use the <=

operator, which means “less than or equal to”. Then to account for when it is a

negative number, we’ll set it to zero within the body of the if statement.

In fight(), inside the while loop#

In the fight() function, find the winner = random.choice() line just above

where we print the updated fighter health. Remove that line and in its place

add the following.

Use an if statement to check if the

rival['health']is less than or equal to0If so

Set the

rival['health']to0Assign the variable

winnertoattacker

144 while winner is None:

145 # pick whose turn it is

146 attacker = fighters[current]

147 rival = fighters[not current]

148

149 # pause for input

150 input(f"\n{attacker['name']} FIGHT>")

151

152 # the attack

153 damage, act = attack(rival)

154

155 # pause for effect, then print attack details

156 time.sleep(DELAY)

157 print(f"\n {attacker['name']} {act} {rival['name']}...\n")

158

159 # pause for effect, then print damage

160 time.sleep(DELAY)

161 print(f"-{damage} {rival['name']}".center(WIDTH), "\n")

162

163 # one more pause before the round ends

164 time.sleep(DELAY)

165

166 # check for a loser

167 if rival['health'] <= 0:

168 # don't let health drop below zero

169 rival['health'] = 0

170 # set the winner, this is now the last round

171 winner = attacker

Part 12. Endgame#

Now that we have a winner, we can tell ‘em they won!

Use some of the concepts you’ve learned to print a nice message congratulating the winner. Try doing it on your own before looking at the code.

Use an f-string to print the name of the winner

Use the

.center()method to center the methodDraw one or more lines by using the

*operator to repeat a string

endgame()

191def endgame(winner):

192 """Takes a PET (winner) and announce that they won the fight"""

193 print()

194 print(f"{winner['name']} is Victorious!".center(WIDTH), "\n")

195 print(winner['pic'].center(WIDTH), "\n")

196 print("-" * WIDTH, "\n")

When you play your game, your fighters will go several rounds before a winner emerges. Your game should end with a nice looking victory message that looks something like this.

Feel free to get creative!

--------------------------------------------------------

Scaley is Victorious!

<`)))><

--------------------------------------------------------